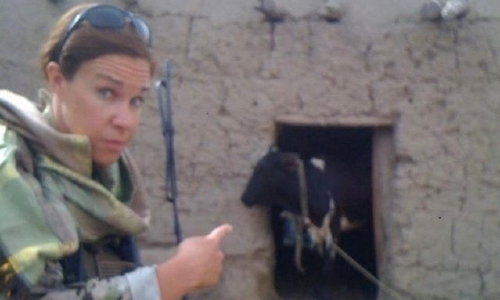

Christine Conley

With brain pledge, Navy Veteran Christine Conley rewrites her story

Navy Veteran Christine Conley courageously served her country for 12 years before taking a medical retirement due to the toll on her body and brain. Afterward, she struggled with symptoms from both post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and traumatic brain injuries (TBI) which made even the simplest of responsibilities incredibly challenging.

Even though every day is still a delicate balancing act, Christine has learned how to cope and manage her daily activities. Below, she shares her story and explains why she decided to pledge to donate her brain to Project Enlist.

Posted: June 28, 2021

By Megan Raphael

Navy veteran Christine Conley has quite a story, but to her, being a part of the Concussion Legacy Foundation’s Project Enlist is the “and’ to it.

For 10 years she had a successful music career in concert and event production as a lighting technician and designer. For a long time, her travels throughout North America satisfied her inquisitive nature and desire to learn more, and she was happy. But then the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon happened. It was at that moment she decided she wanted to do something more, to find a way to give back.

So, at age 27, Conley joined the Navy and was assigned to be part of the military’s law enforcement arm. She spent most of her military career as a criminal investigator and as an instructor in weapons, security, and anti-terrorism.

While deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan she experienced significant injuries, including two events that were later identified as causes of major brain trauma. In one instance, she was inside a building that was hit by explosives and large pieces of rubble hit her on the back of her neck. Another time she was too close to an RPG blast and was thrown up against a door jamb, causing her head to snap back and hit hard. Both times, she did not give the collisions much thought and continued in the action.

Conley was involved in other firefights, too, and her injuries required numerous surgeries.

“I was a hot mess,” she said.

Conley was put on limited duty several times. After those assignments, she was told, “You’re not getting any younger,” and she decided to take a medical retirement; serving 12 years had taken enough of a toll on her body and brain.

It was while she was having some imaging done on her spine in preparation for her retirement that a physician asked if she had had experienced any traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). It was the first time she had ever considered that her earlier head injuries might be the cause of the cognitive and emotional difficulties she was experiencing. And she discovered she was not alone; the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center reports more than 410,000 service members have been diagnosed with TBI since 2000.

For a long time, Conley had been finding it was especially hard finishing sentences and coming up with the right words.

“It was like my brain was on pause. It was a great day if I could make it through getting the words out of my head to my mouth,” said Conley.

She was challenged in completing tasks and started feeling totally undone by bright lights and loud noises. Conley remembers a time when she was grocery shopping and she suddenly felt so completely overwhelmed by the people, the sounds, and the glare of the neon lights that she had to escape the store.

“I didn’t understand what was going on with me, so I had a tendency to push people away or hold them at arm’s length,” said Conley. “I wasn’t getting much sleep and was constantly on edge. My hypervigilance and anxiety were exhausting. I was also grappling with some survivor’s guilt, which- coupled with the guilt I felt seeing my daughter struggle with the impacts of being shuffled around to different friends and family members during my deployments, led to deep depression.”

What Conley was coming up against was what some have called a “perfect storm.” She had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and her symptoms certainly were indicative of that, but she later found out she was also experiencing similar symptoms from her traumatic brain injuries. While PTSD and TBI are separate conditions, this “perfect storm” of both PTSD and TBI can be overpowering and destructive.

“There’s an incredible overlap in terms of symptoms between TBI and PTSD,” said Dr. Rebecca Van Horn, a psychiatrist and U.S. Army Reservist. “The overlap makes it really challenging to determine whether it’s TBI or PTSD causing a particular symptom or maybe it’s both. An individual not only has developed PTSD which is a reaction that occurs after an individual has experienced a trauma, but they also have a physical injury to their brain that has affected the intrinsic functioning of the brain. You have this sort of layering effect of potential structural abnormality in the brain as a result of the direct trauma and you have a behavioral reaction to that trauma in terms of someone’s emotional state and how they interact and function in the world.”

For Conley, life’s simplest responsibilities were more taxing. Her then 10-year-old daughter, Keegan, had to take on many of the adult chores her mother could no longer handle. The toll her problems were having on her daughter were enormous. Reflecting back, Conley says, “Keegan told me, ‘My mom didn’t come back’ [from her deployment]. Keegan had to grow up fast, too fast, out of necessity because I depended on her to step in and help.”

According to the National Center for PSTD and the American Psychological Association, both PTSD and TBI can make a person more difficult to live with, and the recovery can be long and hard on a child or partner. Dr. Van Horn advises any Veteran who believes they may have a history of brain trauma to seek medical care. The CLF HelpLine is also available to caregivers and patients suffering with brain injury symptoms, offering personalized recommendations for support and care.

“An important place to start would be seeing a doctor, having an evaluation of an individual’s history, doing imaging, doing studies to try to understand the nature of the TBI, and then also seeking care for the PTSD,” said Dr. Van Horn. “Several of the treatments for PTSD are also effective at addressing symptoms of depression and anxiety that may be related to TBI.”

Conley tried to seek help but had a very difficult time for many years because, despite medications and treatments, she was not finding the relief she had hoped for. She found some success with other, complementary medicine treatments and today says she feels better than she has in a long time.

“I’ll never be back to who I was, but I’ve finally been able to learn ways to help compensate for the effects from TBI and new ways to function,” said Conley.

The knowledge she gained about the major trauma to her brain which caused her cognitive and emotional difficulties, and the challenges of her search for help, have led her to work with other Veterans. Conley says her path has deepened her passion for helping the military community. The same desire to make a difference that led her to enlist in the Navy is now fueling her work for the Boulder Crest Foundation, an organization working to ensure that combat Veterans, first responders, and their families can live great lives in the midst of trauma.

She sees the toll PTSD and TBI take on the lives of active military and Veterans through her work, and through her friendships. In 2013 she met Ron Condrey and soon after, his wife, Nicole, and they became fast friends. Like Christine, they were committed to giving back to the military community, though in a different manner; both were master skydivers and volunteered at events all over the country. Ron and Nicole’s story, and later Ron’s death by suicide, had a tremendous impact on Conley.

Ron joined the Navy at 17 and was an EOD (explosive ordinances disposal) Tech, as well as a highly trained paratrooper and well-respected leader. He suffered repeated brain injuries from his time around explosives and in combat. By 2015 Ron showed numerous symptoms of TBI, though because his condition was not well understood, he was only diagnosed with PTSD. Nicole told The American Legion Magazine Ron’s condition was plummeting.

“It was like a roller coaster,” said Nicole Condrey. “One day he could be really great and the next day in the dumps. One hour doing great, the next hour not.”

At the time, common knowledge about TBI was just growing. Very often treatments such as the ones Ron received were geared to PTSD, not a dual diagnosis of PTSD and TBI. Ron went down numerous avenues, but none were highly effective. Ron’s condition continued to worsen after retirement, leading him to isolate himself, and even stop skydiving which he loved so much. In September 2018, Ron took his own life at the age of 45.

Conley had numerous discussions with Ron and Nicole before Ron’s death about what he was dealing with. Because she was having her own struggles with TBI, she could relate. Once when she asked him how he was doing, he replied, “I’m not doing good.” His honesty got her attention, and though she knew something was not right, she did not fully realize the depth of his pain. His death woke her up to how brain trauma was affecting so many of the people she had deployed with, and she became interested in the research being done to help solve the invisible wounds of war.

“Ron’s death hit so close to home,” said Conley. “It was a sobering reminder that it could happen to anyone of us because of our head injuries.”

She was aware of Nicole’s decision to donate Ron’s brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, and she began thinking about it for herself. She read up on Project Enlist, CLF’s program which aims to serve as a catalyst for critical research on TBI, CTE, and PTSD in military Veterans by encouraging brain donation. She learned that studying donated brains will help researchers better understand how military brain trauma uniquely leads to brain disease and how to diagnose and treat it.

Nearly 8,000 people have pledged to donate their brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, including more than 1,600 military service members and Veterans. Project Enlist is actively recruiting military Veterans who are willing to pledge to donate their brain, whether or not they have a history of brain trauma, to support the ongoing research. By signing up, participants can also learn about clinical studies they may be eligible for during life.

“There is exploration and discovery in neuropathology that is not possible with neuroimaging,” Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, told The American Legion Magazine. Dr. McKee is also the director of the National PTSD Brain Bank and published the first ever case series on CTE in the military.

Once Conley understood the impact of TBI and CTE on her beloved military community, and how she and other Veterans could accelerate research, she stepped up and pledged to donate her brain to Project Enlist.

“If this is the only way to get answers, I’ll do it,” said Conley. “The truth is you can’t take [your brain] with you. I figure no matter what else you’ve done in your life – whatever selfish deed – this is an opportunity to do what’s good at the end. This is my living legacy because I know it’s going to make a difference and help others as they live. I have a story as we all do, but this is my AND. This is what comes after my story and it’s a good and.”